#2: The Magical Kilowatt-Hour

A quick summary of where we left off last time:

To reduce greenhouse gas emissions we need to first focus on our energy system, which contributes over 70% of total greenhouse gases.

Our energy system is made up of producers and consumers.

Our plan is two fold: Take steps to 1. increase electricity production (producers) from renewable sources and 2. electrify our energy consumption (consumers).

A history of energy

Everything we’ve ever accomplished as a species has come from being able to harness energy. For most of human history, most of the energy we used on a daily basis came from our muscles (living), domesticated animals (farming), and burning wood (heat). The industrial revolution brought us the ability to harness energy at an industrial scale.

Our energy sources have also been constantly evolving:

In 1500’s your energy came mostly from 4 places:

Livestock

Firewood

Coal

Your muscles (which is powered by the food you eat, I guess)

Someone living in year 2000 would’ve consumed energy via

Natural Gas

Electricity

Oil

Coal

Unfortunately, the way we measure the amount of these sources are different, so it makes it difficult to compare. For instance, natural gas is measured in Cubic feet, while oil is measured in barrels. Coal is measured in tons. Then byproducts of oil, like gasoline are measured in gallons. This makes comparisons between different energy sources difficult. We need to standardize on a common measurement.

The kilowatt-hour

The unit we will be measuring energy with from this point forward will be a kilowatt-hour (kWh). It’s worth spending a bit of time here to understand this. Let’s use the analogy of filling a bathtub with water. A kilowatt is a measure of a rate of energy transfer, also called power. In our bathtub analogy, this is equivalent to how fast the water is flowing out of the faucet. The higher you turn up the faucet, the higher the flow is.

A kilowatt hour therefore, is the total amount of power transferred after 1 hour. This would be equivalent to how much water is in the tub, after keeping the faucet on for a full hour.

(In this sense, it’s non-sensical to say “number of kilowatts per hour”, since it’s already including time. It would be like saying miles per hour per hour).

Conceptualizing 1 kWh

A kWh is a good reference point because humans tend to use energy on the scale of kWh’s. (We also get billed by electric companies based on the number of kWh we use per month). Here is how many kWh some of our daily appliances use:

These popular Amazon 8.5W light bulbs consumes 0.2 kWh over 24 hours (0.0085kW * 24 hours)

A typical dishwasher run consumes 2 kWh

A 50 inch LED TV would consume about 0.4 kWh if left on for 24 hours

The average American uses 219 kWh of total energy a day

The average American uses 28 kWh worth of electricity a day

The 2021 Tesla Model 3’s battery can hold 82 kWh, which can go 350 miles on a single charge. This comes out to 4.2 miles / kWh.

Everything I mentioned used energy in the form of electricity. Let’s do a few more examples of non-electric energy usage.

A Toyota Prius is one of the most fuel efficient cars on the market. It can get 54 mpg. One gallon of gasoline contains 36 kWh of energy. This comes out to about 1.5 miles / kWh.

The average home in the US uses 168 cubic feet of natural gas for heating, water heating, and cooking. 1 cubic feet contains 0.29 kWh. This is about 49 kWh worth of energy.

The average cost of these sources of power are different in each state, but here are some US national averages:

The cost of electricity: 13.1 cents / kWh

The cost of natural gas: $10.6 / 1000 cubic feet = 3.6 cents / kWh

The cost of gasoline: $2.5 / gallon = 6.9 cents / kWh

The cost of coal = 3.2 cents / kWh

The relative rates of these sources will matter.

So how much energy do we use?

Wikipedia shows a detailed list of how much energy we need to produce per capita in different countries. Here is a map of our energy consumption.

In Summary

All sources and uses of energy can be measured in kWh

From now on, the kWh is what we will use to standardize all our measurements of energy.

Different forms of energy are different prices. 1 kWh of natural gas is currently much cheaper than 1kWh of electricity.

Next Time…

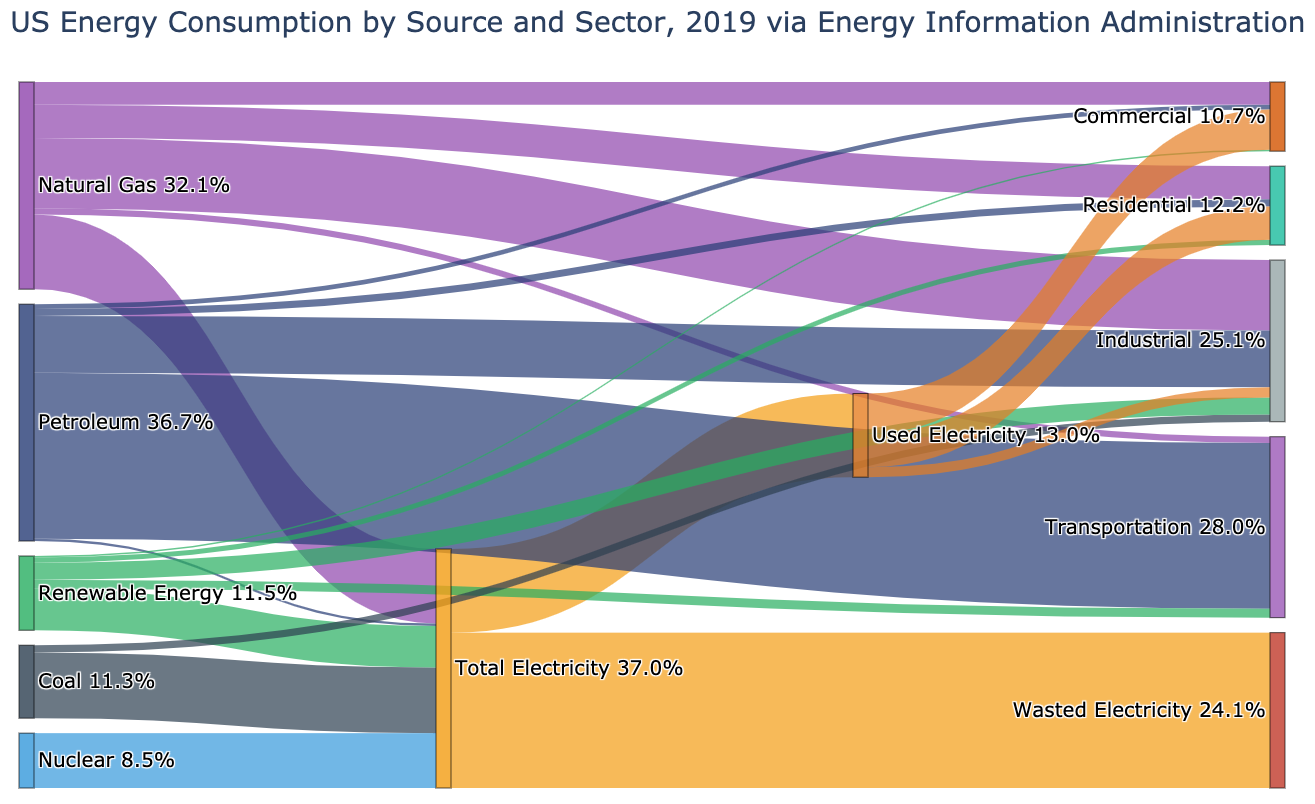

In the next post we’ll come back to this graph of our energy:

And see what it looks like after once we start massively scaling up our wind production with onshore wind turbines.

If this was interesting to you, and you want to stay in the loop, sign up for the newsletter: